The Gate saw

Timber was exported from Norway as early as the 1100s. The first water-powered sawmills appeared in the late 1400s in southern Norway and around the Oslo Fjord. The gate saw gets its Norwegian name, oppgangssag, from the up-and-down action of its blade. These saws led to a more efficient production of wooden planks and boards. Wooden floors and ceilings now became more common in houses with fireplaces, and siding was laid on older houses built of logs.

A sawmill could only be built near a millpond that allowed for a fall of at least four meters. Sawmills were divided into one of four categories according to their water supply. A year-round saw stood in a river that could power it all year long, at least in frost-free months. The flood-saw and the smaller brook-saw could be used only when brooks and rivers flooded in spring and fall. The smaller waste-water saws were powered by water coming from other saws.

Timber was one of the country’s most important exports in the 1500s and 1600s. First transported on foreign ships, the trade then became the foundation for an independent Norwegian shipping industry. Sawmilling had been open to anyone, but the ordinance on sawmilling privileges in 1688 set quotas for export mills and restricted ownership to merchants in towns. Before 1688 there had been 1200 sawmills in operation, but the number was reduced to 664 after the ordinance became effective. Sawmilling privileges remained in force until 1860.

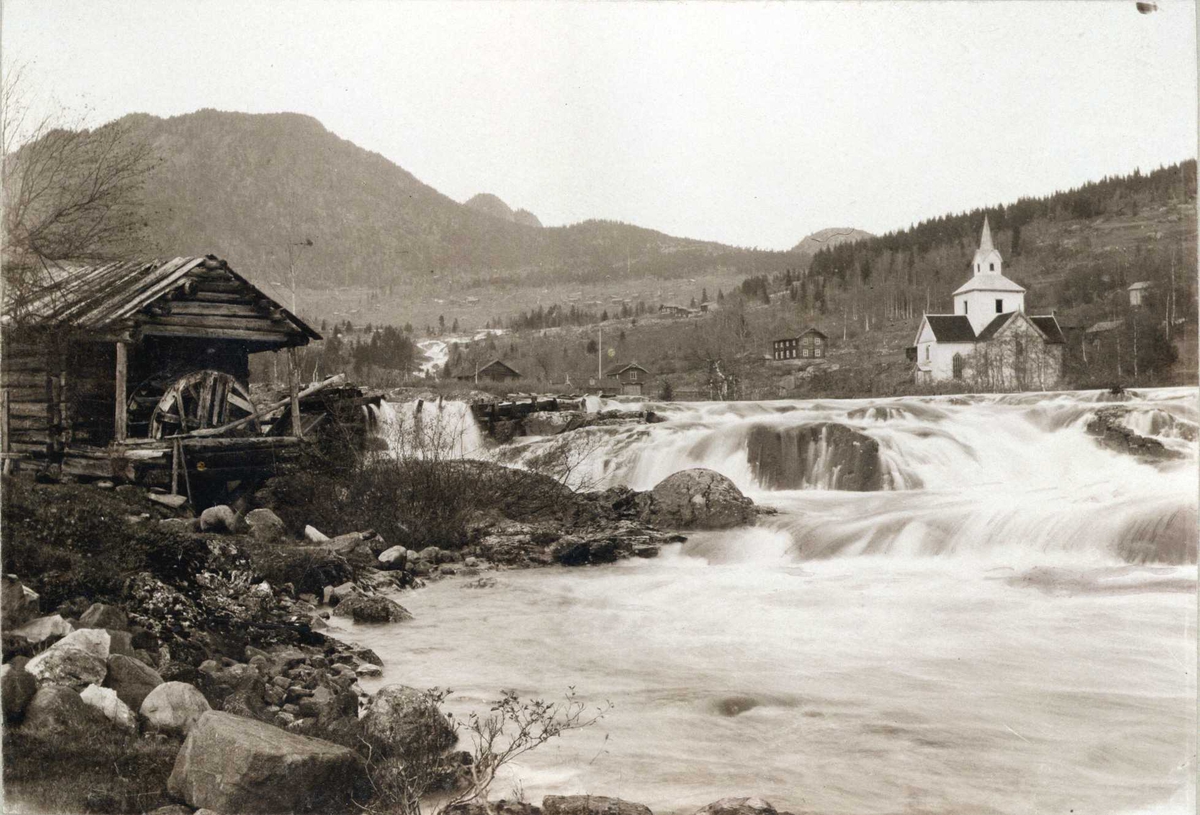

Image from digitaltmuseum.org

Image from digitaltmuseum.org Gate saw from Åkra (Ullensvang, Hardanger, 1700-1800)

This sawmill is a simple timber-frame building built on a bulwark of logs and stone. Its large waterwheel works the saw. A smaller waterwheel that can be lifted up or down draws the log back, while a third, larger waterwheel hauls the logs up to the saw from the fjord below.

The Åkra sawmill got its privilege in the early 1700s. This is a one-bladed sawmill with a capacity of probably three to four boards an hour. The sash saws that appeared in the late 1700s had up to eight parallel saw blades.

Fulling Mill

Another water-powered invention is the fulling mill, which was used in the making of a felt-like cloth. Woollen cloth was put in a tub and warm water poured over it. The water wheel was activated, and the cloth pounded by the fulling stocks. When the process was finished, the cloth was rolled onto a round pole.

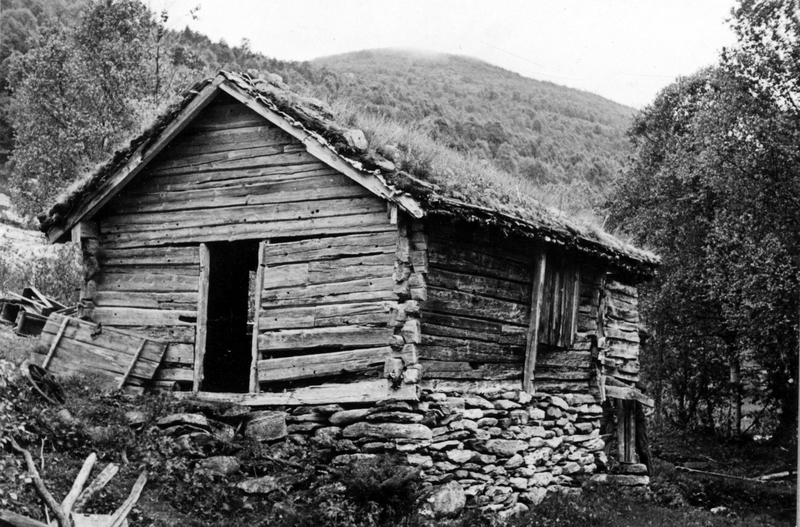

Image from digitaltmuseum.org

Image from digitaltmuseum.org Fulling mill from Jøssvoll (Stordal, Sunnmøre, 1850-1900)

The building was once a smoke-oven farmhouse. Marks after the smoke vent can be seen on the rafters. The smoke oven stood in the corner by the door.

The house was re-built as a fulling mill by Mons Jøsvoll in the latter half of the 1800s and used until 1910. Mons Jøsvoll’s father and grandfather were both fullers.

Watermills

Most farms had their own water-powered mill, often lying one after the other along larger streams. Use was usually limited to spring and fall when enough water flowed down the stream.

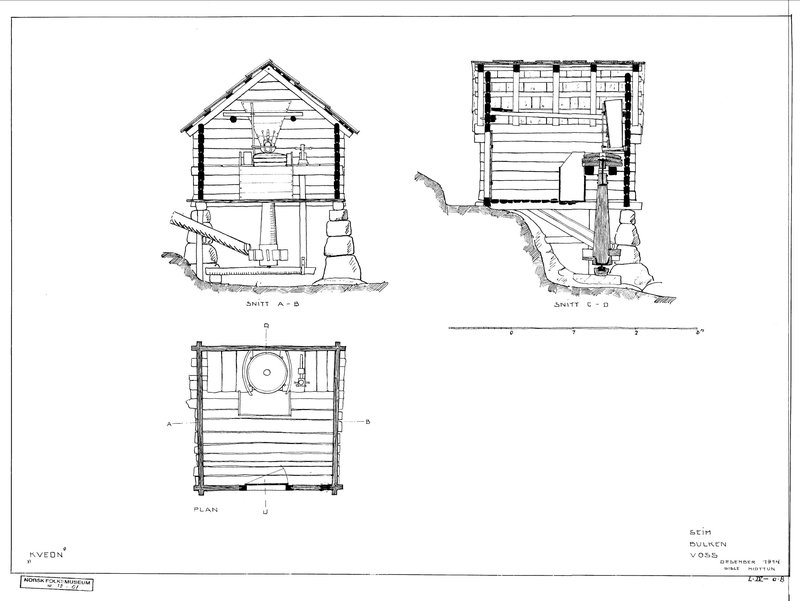

Image from digitaltmuseum.org

Image from digitaltmuseum.org Mill from Harstad (Valle, Setesdal, 1500s)

Grain was poured into a funnel and water was led into rhe water wheel, or kvernkalle, to make the upper grindstone revolve. The grain ran from the funnel down into a little trough lower down and from there through a hole, the kvernøye, in the stone. As the grain was crushed and ground into flour, this was then collected in a flour bin.

Image from digitaltmuseum.org

Image from digitaltmuseum.org Mill from Seim (Voss, ca. 1800)

This mill resembles the one from Setesdal, in both equipment and appearance, even if more than 200 years separate them.